The idea came to Sam Cooke on the evening of April 12, 1962, when he appeared at Atlanta’s Rhythm Rink while on an extended Henry Wynn Supersonic Tour of the South. The King of Soul was headlining a lineup that included blues legend Solomon Burke, the Drifters, Dee Clark, B. B. King, and Dion DiMucci (of Dion and the Belmonts’ fame).

At that time, racial tensions percolated just as the civil rights movement gained momentum. Thus, a “mixed-race tour” in the Old Confederacy generated a wellspring of controversy. Cooke’s biographer, Peter Guralnick, remembered: “Sam was the soothing influence who kept that tour together. ‘He was a kind of champion for… cooling everybody out,’ said Dion DiMucci, and, as on the earlier tour, some of Dion’s most treasured memories were of singing with Sam backstage—” he was always so full of music.'”

According to Sam Cooke’s friends, the notion of the song had been stirring around in the singer/songwriter’s mind for weeks. The idea’s inspiration had actually sprung from soul singer Charles Brown’s 1959 R&B single, “I Want to Go Home,” a standard 12-bar blues number ladened with traditional call-response that had also been sautéed in a barrel full of soul.

Cooke, who had been a gospel music prodigy before he was 18, had spent much of the preceding ten years on the road, though he now made Los Angeles his base. For someone who was a Chicagoan for more than half of his life, home had become not a physical place for Sam – but it was “about the people you left behind.” This was especially evident to him because he had lived his musical career out of a suitcase.

As Sam Cooke rode in a rented limousine to the concert that evening in Georgia’s capital city, it all came together for him. He yearned to write a gospel-tinged blues song featuring call-response in the form of a “backside” duet – a lead singer in concert with a strong vocal response. Of course, this wasn’t some new form of music for him. Instead, Cooke instinctively yearned to compose the same style of music when he joined gospel’s legendary Soul Stirrers beginning in 1949 before he had finally crossed over to the dominion of rock-pop with 1957’s “You Send Me.”

While the white public hardly knew of Sam Cooke during his halcyon years as a gospel icon, he had already achieved mythical status to millions of African-Americans around the country while he was the leader of the Soul Stirrers. In 2016, Aretha Franklin recalled Cooke’s magnetism as a gospel star:

“Sam and I met at a Sunday evening program that we had at our church back in the early ’50s. I was sitting there waiting for the program to start after church, and I just happened to look back over my shoulder, and I saw this group of people coming down the aisle. And, oh, my God, the man that was leading them — Sam – and his younger brother, L.C. These guys were really super sharp. They had on beautiful navy blue and brown trench coats. And I had never seen anyone quite as attractive, not a male as attractive as Sam was. And so, prior to the program, my soul was kind of being stirred in another way. And then, Sam sang, and he left everything, everything out on the stage. He was the most beautiful man I ever saw.”

Sam Cooke’s live performances as a gospel lead singer became so renowned that he was compared in real-time to Frank Sinatra in terms of influence, magnetism, and sheer luminosity. Thus, when he eventually entered the world of pop and soul, his loyal gospel fans viewed him as a Judas. However, once he began churning out such original standards as “Wonderful World,” “Chain Gang,” “(She Was) Only Sixteen,” Everybody Loves to Cha Cha Cha,” “Sad Mood Tonight,” “Cupid,” Twistin’ The Night Away,” and “Feel It,” all was eventually forgiven.

Thus, when he alighted from the limousine that night in Atlanta and rushed for the stage, Sam couldn’t shake this “back home idea,” as he called it. Cooke knew that he had to compose and record it quickly. After the concert that evening, he composed much of it in his downtown Atlanta hotel room. Like the vast majority of the numbers he wrote, the refrain section of the song came to him first: “Bring it to me, bring your sweet lovin’, bring it on home to me.”

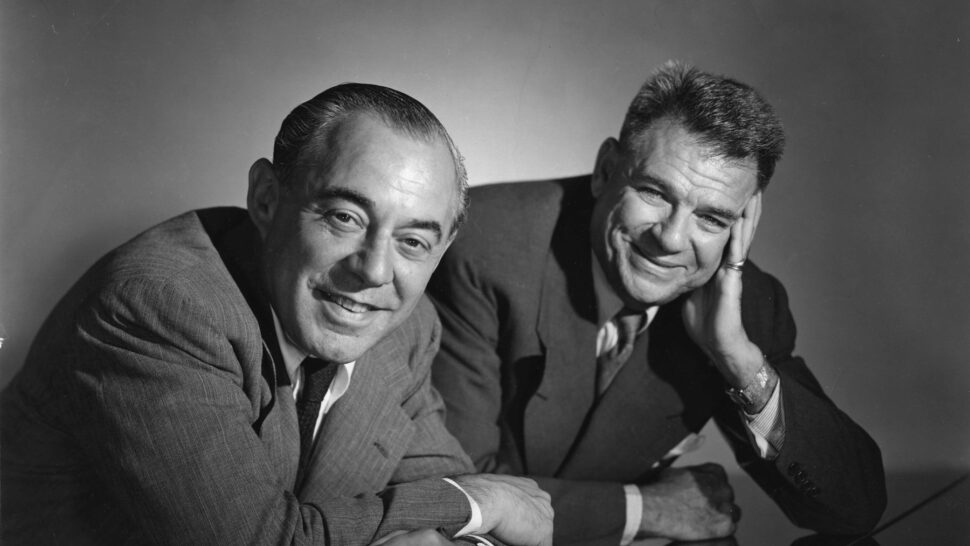

Once he completed the number, Sam felt it had a bluesy, almost hypnotic feel, which excited him that he sang it to performer Dee Clark, whose single, “Raindrops,” had been a significant hit the previous summer. Clark wasn’t impressed at first, but Cooke felt he had something, so he then called his producer back in California, Luigi Creatore, who immediately loved the concept. Sam kept emphasizing that he wanted to sing and record it in the vein of his old Soul Stirrers gospel hits, and Creatore readily agreed.

Given that the singer/songwriter had already composed a ready-made single, “(We’re) Having a Party,” Cooke and his producer thought that the now-titled “Bring It Home To Me” would fit nicely as its B-Side.

By the time Sam made it back to Los Angeles from his Southern tour ten days later, the number was ready for recording. On April 26, 1962, Cooke entered RCA’s Recording Studio Number 1 in Hollywood, anxious to record both “Having a Party” and “Bring It Home To Me.” Awaiting him were the customary Wrecking Crew musicians, including Tommy Tedesco on lead guitar, Adolphus Alsbrook on the bass, Ernie Freeman on the keyboards, and a bevy of acclaimed string players who had long backed up Sinatra on such hit albums as In The Wee Small Hours of The Morning and Only The Lonely.

The assemblage of musicians began the session with Sam’s “(We’re) Having a Party,” the designated “A-Side,” which was the musical stepchild of his smash hit, “Everybody Loves To Cha Cha Cha.” Cooke’s longtime arranger, René Hall, had not only transposed both numbers to be accompanied by six violins, two violas, two cellos, and a saxophone, but he had also added a seven-piece rhythm section to the mix. “We wanted musical power to match Sam’s vocal potency,” Hall remembered.

That night, Cooke was joined by the Sims Twins, a novice vocal group he had signed with his newly-formed SAR Records the previous year. At the last minute, Sam also asked one of his childhood friends from Chicago, Lou Rawls – whose plush bass-baritone voice had constantly demanded recording sessions around LA since he moved to the West Coast in 1959 – to sit in on the session as well. “We might need you, Lou,” he winked to his longtime friend as he entered the studio.

After pushing through the infectious “Having a Party,” which took 13 takes to make right, Cooke huddled up with René Hall to continue the good vibes and momentum after they recorded “Party” with “Bring It Home To Me.” Later on, he told his former producer, Lou Adler, “We were after the Soul Stirrers-type thing, trying to create that flavor in a classic rhythm and blues recording.”

“Let’s get to it! “Sam exclaimed to the musical entourage assembled at the studio. In just two takes, that’s exactly what they did. Cooke reflected later that it was probably because he yearned for a “live feel” to the ballad. “I wanted it to feel just like a Soul Stirrers’ performance on stage.”

Sam and his production team encouraged renowned pianist and bandleader Ernie Freeman to provide the number’s “intro” with a blues riff that would instantly capture the attention of any listener. After fiddling around on his keyboard for a spell, Freeman crafted a hypnotic, primal introduction that ultimately became a chilling calling card to Sam’s distinctive tenor. Freeman’s bluesy keyboard riff was then supported by the counter-punching percussion chops of Frank Capp, a veteran Wrecking Crew drummer. This pulsating ostinato proved to be an electrifying prologue to one of Sam Cooke’s two or three most revered vocal performances of his storied career.

“If you ever-er change your mi-ind

About leavin’, leavin’ me behi-ind

Oh-oh, bring it to me

Bring your sweet lovin’

Bring it on home to me-ee…”

Just four bars into it, you knew it was Sam Cooke. While he earned the moniker “The King of Soul” after his untimely death in 1964, in the spring of ’62, you could have predicted that such a dominating vocal performer paved the way for a thousand branches. Like the chiseled knife that can cut your soul in two, the singer’s vocals are wrapped in a cornucopia of both fidelity and pain throughout the ballad.

To put the finishing touches on the gospel-like feel, Lou Rawls not only sings harmony with Sam, but he then bestows a series of muscular call-response “yeahs” throughout the recording as well. In the end, Rawls’ heady vocal conviction and entusiasmo are such that he nearly hijacked the tune from Cooke in the process.

Once the last note was played in LA’s RCA Recording Studio Number One, everyone involved knew even then that they had cut something special. It had taken them only two takes to get it right. This was not Sam Cooke, a pop star to a largely white audience. This was Sam Cooke, master of both gospel and soul. As Peter Guralnick remarked in his exceptional biography on Sam Cooke: “What comes through in ‘Bring It Back Home To Me’ is a rare moment of undisguised emotion, an unambiguous embrace not just of cultural heritage but of an adult experience far removed from white teenage fantasy. There was nothing to add or subtract.”

Arranger René Hall recalled years later. “There was minimal post-production that went into that song. We took it out of the oven, and it was ready for wax.” It had taken less than 30 minutes of studio time to craft a definitive soul ballad sung by two of the greatest R&B performers of all time, even as it was superbly backed up by LA’s celebrated Wrecking Crew. Of course, enduring artistry is never an accident.

Released along with “Having A Party” on May 21, 1962, by RCA Victor, “Bring It Back Home To Me” was “discovered” by a legion of deejays who methodically played Cooke’s “B-Sides” in case there was something there.

There was.

By the early summer of ’62, “Bring It Back Home To Me” began to enter national top-ten lists, reaching as high as #2 on the R&B list and #13 on the pop charts. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who was an avowed Sam Cooke fan, cried, “My goodness, what a sound!” to his friend, the Reverend Ralph Abernathy, when the two civil rights leaders drove to a conference outside of Atlanta one afternoon that summer and heard it on the radio.

Over the years, “Bring It Back Home To Me” was famously covered by both John Lennon and Paul McCartney during their post-Beatles solo careers. It also found favor in both the recording studio and/or onstage with the likes of James Brown, The Animals, Van Morrison, Rod Stewart, Bonnie Raitt, UB40, Bruce Springsteen, Southside Johnny & The Ashbury Jukes, Al Jarreau, Goerge Benson, and U-2. While Sam Cooke was tragically murdered less than three years after this seminal recording, “Bring It Home To Me” is still so revered by musicians that Tom Petty called it “sacred” when he chatted about its timelessness on his Sirius Radio show back in 2016.

In retrospect, gospel drove Sam Cooke through his most celebrated songs the same way it did for Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, and Otis Redding. Like the legendary Nat Cole, Cooke had an incomparable voice that is as distinctive as a fingerprint. In retrospect, Sam could sing anything and make it work. As the late Lester Bangs once famously wrote in Crawdaddy, “It was his power to deliver — it was about his phrasing, the totality of his singing, which made him immortal.”

Of course, Sam Cooke could have sung out the names of the street signs in his hometown of Chicago, and it would have sounded great.